The Cold Truth: Should You Really Store Batteries in the Fridge?

Why Battery Storage Matters—and What This Guide Covers

Open a kitchen drawer in almost any home and you’ll find a small library of cells: cylindrical alkalines rolling beside a pack of rechargeables, a coin cell for a scale, maybe a power tool battery tucked in the back. They quietly power remotes, flashlights, toys, cameras, radios, alarms, and backup gear you count on when the lights go out. That’s why the question “Should I put batteries in the fridge?” matters. It isn’t just trivia; storage can affect safety, lifespan, and how ready your devices are when you need them. This introduction sets the stakes and explains the path we’ll take to convert a hand‑me‑down tip into a clear, science‑backed plan you can use today.

Here’s what this guide will cover, and how each piece fits together for everyday decisions:

– A quick outline to orient you before we dive deep

– How temperature changes battery chemistry, capacity, and self‑discharge

– The actual pros and cons of refrigerating batteries (and why the answer isn’t one‑size‑fits‑all)

– Practical, room‑temperature storage routines that prevent leaks, reduce risk, and keep devices ready

– A closing rule‑of‑thumb so you can decide, at a glance, what to do in your home

Along the way, we’ll keep the focus on common types you encounter in real life: alkaline, zinc‑carbon, primary lithium (non‑rechargeable), nickel‑metal hydride (NiMH), nickel‑cadmium (NiCd), and lithium‑ion (rechargeable). We’ll translate lab‑bench ideas into daily habits, like how to bag and label spares, how full to store a rechargeable, and when cool storage is helpful versus needless. Expect plain language, a few numbers where they add clarity, and practical examples, such as preparing emergency kits for a storm season or maintaining a set of camera flash cells for occasional events. By the end, you’ll have a calm, practical approach that trades myths for measured habits.

Chemistry 101: Temperature, Self‑Discharge, and Shelf Life

The heart of the fridge myth is partly true: chemical reactions slow down when it’s cooler. A rule of thumb drawn from kinetics says many reaction rates roughly double for every 10 °C rise in temperature, and the inverse is also broadly true. That matters because batteries age through small, parasitic reactions that consume active materials and through self‑discharge that bleeds energy over time. Cooling can tamp down both. But the details depend on chemistry, and that’s where blanket advice falls apart.

Alkaline cells are ubiquitous because they’re affordable, stable, and tolerant. Their self‑discharge at room temperature is relatively low—often just a few percent per year—supporting shelf lives of five to ten years when stored in a cool, dry place. Primary lithium cells (the non‑rechargeable kind used in many high‑drain or cold‑weather applications) are even more stable, often well under 1% self‑discharge per year, with long dated shelf lives. For these chemistries, moderate cooling can reduce already small losses, but the absolute gain may be modest in a household that sits between 15–25 °C.

Rechargeables tell a different story. Traditional NiMH cells can self‑discharge quickly at room temperature—historically up to a few percent per day right after charging—though modern low‑self‑discharge variants have tamed that to on the order of 10–30% per year under favorable conditions. NiCd behaves similarly in trend, if not always in magnitude. Lithium‑ion is a special case: its self‑discharge is modest (commonly a few percent per month), but it also experiences “calendar aging” that depends strongly on state of charge and temperature. High temperature and high state of charge accelerate loss of capacity over time; cooler and mid‑level states of charge slow it down. That’s why guidelines often recommend storing lithium‑ion around 30–60% charge and keeping it near 15–25 °C for long pauses.

Cold introduces trade‑offs beyond slower reactions. Internal resistance rises at low temperature, so a cold battery may sag in voltage and appear weak even if it still contains energy. Once warmed to room temperature, much of that performance returns. Extreme cold can also thicken electrolytes, stress seals, and in some chemistries risk damage if actually frozen. Conversely, heat is consistently unkind: temperatures above about 30 °C accelerate chemical side reactions, dry out electrolytes, and increase leakage risk in some primary cells. In other words, for most households, avoiding heat is far more impactful than seeking extra cold. A steady, moderate room temperature paired with dryness usually gives you the lion’s share of longevity without introducing new risks.

– Heat accelerates aging; cool moderates it, but cold can hinder performance on demand

– Different chemistries respond differently; a single rule is misleading

– For lithium‑ion, storage charge level matters as much as temperature

– For alkalines and primary lithium, gains from refrigeration are often small relative to the hassle and risk of moisture

The Fridge Debate: Advantages, Risks, and When It Might Make Sense

Let’s put the rumor under a microscope. Why would anyone chill batteries? Because lower temperatures can reduce self‑discharge and slow aging reactions. If you’re holding a stockpile for long periods—say, a year or more without use—cooling might preserve a little extra charge. In a warehouse with carefully controlled humidity and packaging, that effect is predictable. In a home refrigerator packed with produce, humidity swings, and frequent door openings, the story changes. Moisture condenses on cold surfaces when warm air hits them, and batteries are small metal cylinders with seams, caps, and labels—all places condensation can gather and, over time, creep into trouble.

The advantages are straightforward but limited in scope. A sealed, unopened pack of alkaline or primary lithium cells placed in a stable, cool environment will lose charge more slowly than the same pack at a higher temperature. If your house routinely reaches 30–35 °C for months and you lack climate control, the relative benefit of a cooler spot grows. In rarer cases—like staging emergency supplies for an extended deployment in a hot region—refrigeration under strict packaging discipline can make sense.

The risks deserve equal airtime. A typical refrigerator is humid inside. Opening the door cycles temperature and invites moist air, which condenses on colder contents. If you place loose batteries inside without protection, droplets can form on metal surfaces, promote corrosion at the seams, and contaminate labels. With rechargeable lithium‑ion packs, condensation around exposed contacts is especially unwelcome. There’s also the human factor: items stored in the door experience the largest temperature swings; containers get shuffled; and a family member might open a sealed bag before the batteries have warmed, inviting condensation inside the packaging.

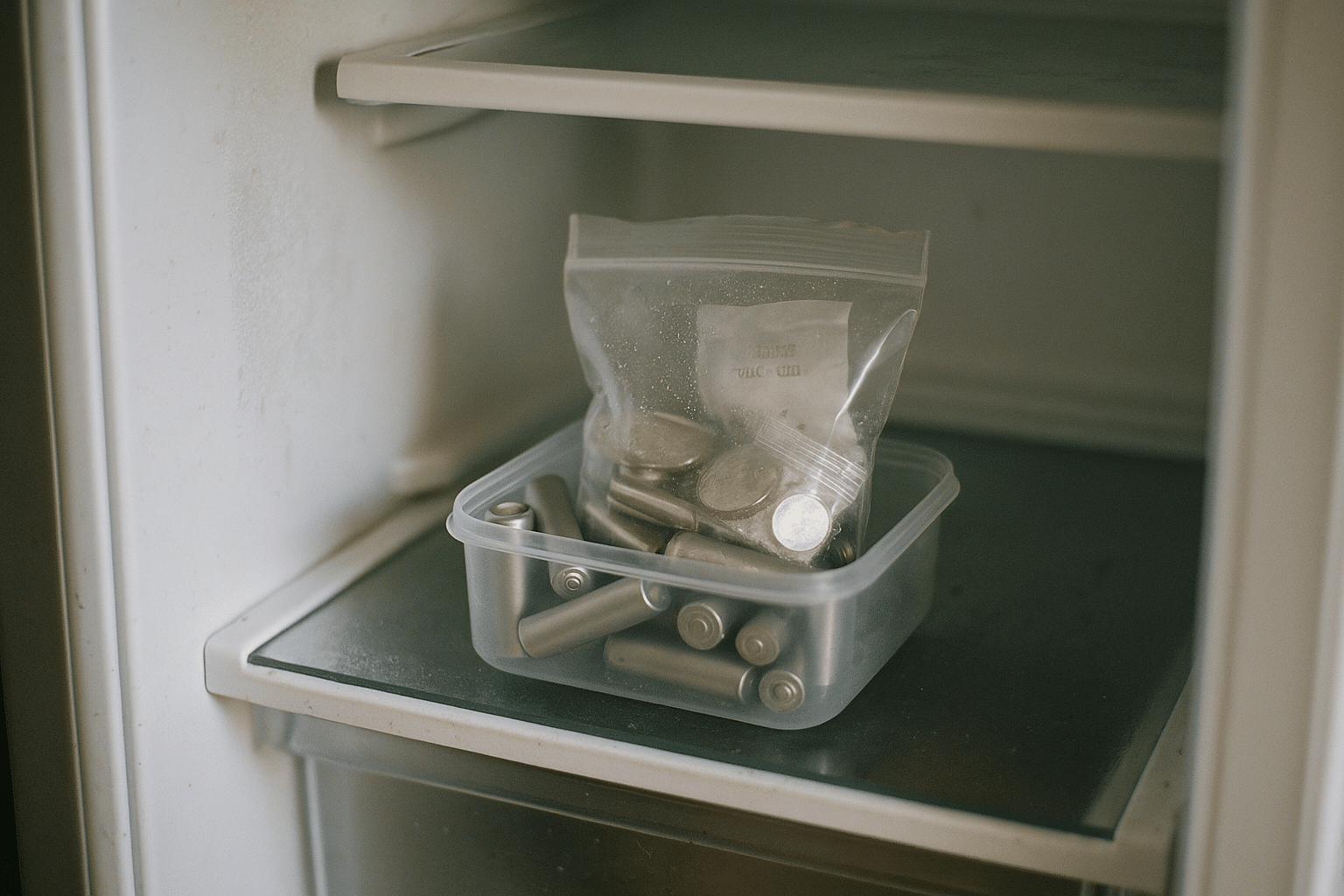

There is a narrow, disciplined way to do it if you must. Store only sealed, undamaged batteries. Place them in an airtight bag with a desiccant pouch, expel excess air, and label the bag with a date. Put the bag in the coldest, most stable part of the fridge—not the door—and keep them away from food. When you’re ready to use them, remove the sealed bag and let it warm to room temperature before opening, so moisture condenses on the outside of the bag, not on the cells. Never refrigerate batteries showing signs of leakage or damage, and do not use a freezer unless a chemistry’s datasheet explicitly allows it; extreme cold raises the chance of damage and condensation upon thawing.

– Refrigeration can help if your ambient temperature is persistently high and packaging is airtight

– Condensation is the chief household risk; temperature cycling inside a fridge increases it

– Freezers are generally unnecessary and raise the stakes for moisture and mechanical stress

– For most homes at 15–25 °C, a dry closet beats a refrigerator on practicality and safety

Home Storage That Works: Simple, Reliable Practices

For most people, the smartest path is steady, moderate, and dry—not cold. A shelf in an interior closet typically beats a garage or attic, which can swing from chilly to hot in a single day. Keep batteries organized, isolated from metal objects, and labeled so you don’t mix old with new. A small, non‑conductive container with dividers prevents accidental short circuits, especially for loose cells with exposed ends. Original packaging is fine; so are protective caps and cases for rechargeables. The goal is predictability: temperature that drifts little, humidity that stays low, and contact protection that stops a coin cell from bridging a keyring or two AA cells from touching a stray screw.

Tailor storage to chemistry and use pattern:

– Alkaline and primary lithium (non‑rechargeable): Store in a cool, dry place around 10–25 °C. Keep in original packaging until needed to avoid shorting and to reduce handling. Do not mix old and new cells in a device; replace as a set to avoid leakage or reverse charging. Check devices during long storage and remove batteries from rarely used items to prevent forgotten leaks.

– NiMH and NiCd (rechargeable): If used frequently, store charged and top up before use. For multi‑month storage, modern low‑self‑discharge NiMH can sit charged; check quarterly and recharge as needed. Avoid leaving cells fully depleted for long periods. Keep contact caps on and avoid metal containers that could bridge terminals.

– Lithium‑ion (rechargeable): For storage beyond a few weeks, aim for roughly 30–60% charge, and keep at 15–25 °C. Check every few months and recharge to the mid‑range if the level has drifted down. Avoid parking packs at 100% for months or allowing them to sit near empty, both of which accelerate aging. Keep packs away from heat sources and direct sun.

Adopt a simple maintenance routine. Label new packs with the purchase month. Rotate older stock forward so the oldest gets used first. Inspect for swelling, corrosion, or damaged wrappers; set aside any suspect cells for proper recycling. Keep a small desiccant pouch inside your storage bin if you live in a humid climate. Separate coin cells in sleeves or small envelopes to avoid accidental shorting. For emergency kits, review contents at the start of each season and replace items nearing end of shelf life.

Safety is part of storage. Do not toss damaged or depleted batteries into household trash; use community recycling programs or retailer drop‑off bins to avoid fire risk and environmental harm. Cover terminals of larger rechargeable packs with non‑conductive tape before transport to a recycling point. Never store loose cells in pockets, toolboxes, or junk drawers where metal objects can bridge terminals. If a device will sit unused for months, remove its batteries and store them in your organized bin instead.

– Choose stable, indoor locations over kitchens, garages, and attics where temperatures swing

– Keep cells separated and capped; original packaging is useful protection

– Label, rotate, and inspect on a schedule; small habits prevent big problems

– Recycle responsibly; do not stockpile damaged cells

Conclusion: A Clear Rule of Thumb for Everyday Users

If your home stays roughly between 15–25 °C, you rarely need a refrigerator for battery storage. You’ll gain more by keeping batteries dry, protected from shorts, and organized by chemistry and age. Alkaline and primary lithium cells already have slow self‑discharge at room temperature; refrigeration may trim a small percentage, but it also invites moisture risks unless you package meticulously. Rechargeables benefit most from correct state‑of‑charge storage and avoidance of heat rather than from cold. In normal households, a calm closet shelf outperforms a busy fridge on both convenience and reliability.

There are edge cases. If you live in a hot climate without cooling and room temperatures sit above 30 °C for long stretches, refrigeration can be a justified strategy for unopened, sealed primary cells, provided you follow strict moisture control: airtight bag, desiccant, stable placement away from the door, and a patient warm‑up before opening. Even then, avoid freezing and think twice for lithium‑ion, where charge level and avoiding heat are the dominant factors for longevity.

The takeaway is simple enough to remember: keep batteries cool, not cold; dry, not damp; and stored in a way that prevents accidental contact. Match storage to chemistry—mid‑charge for lithium‑ion, routine check‑ups for NiMH, and common‑sense handling for alkalines and primary lithium. With those habits, your devices will wake up ready when you press the button, without you having to turn your fridge into a battery locker.

– For most households: a dry, interior closet is the practical choice

– Use refrigeration only for specific, hot‑climate scenarios with sealed packaging and careful handling

– Prioritize safety: no loose cells near metal, and recycle damaged or spent batteries promptly